Thank you Rebecca for convening a very timely discussion. Thanks also to you, Mark Abrahamson and your teams for your thoughtful research on some of the issues I will touch on today, especially around the value of data.

The emergence of political risk in developed countries after 70 years, is more than a line to mitigate on our risk registers. It has prompted us to reflect on a different approach to our role as businesses and leaders in the economy and in society.

Today’s panels will cover many of the trade-offs that preoccupy us.

I want to consider some trends in technology that provide part of the backdrop to these challenges.

Lessons from globalisation

As has been said many times, we can trace a large part of today’s political disruption to a backlash against globalisation and the financial crisis that followed.

While the gains of globalisation were widespread, indirect and incremental, the pain was local, direct and acute.

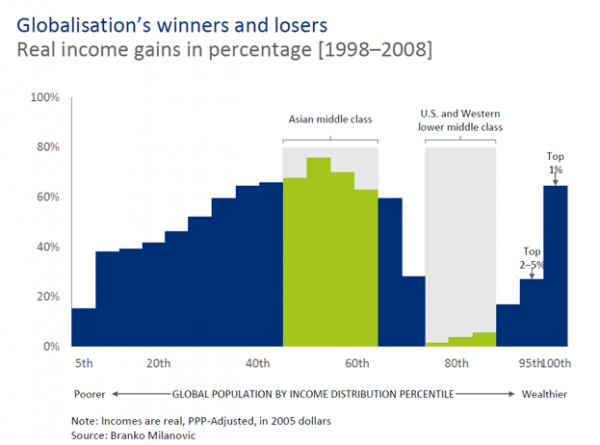

The big winners were the elite global one percent and the working and middle classes in Asia, while the losers were the working and middle classes in the West.

The lesson is not that we should put the genie of globalisation back in the bottle.

Rather, the lesson should be that a global and broadly positive impact of change, should not allow us to neglect and be insensitive to the painful consequences of dislocation and disruption felt by people and communities closer to home.

Even as we grapple with the fallout from that failure to manage the forces of globalisation, we are in the midst of a fresh tide of technological disruption which has the potential to exacerbate problems not yet solved.

We’ve not learnt to ride the tiger of disruptive economic forces. But have the potential to repeat and compound those mistakes.

The current debate on technological disruption is rightly centred on social issues, including pluralism and democratic discourse, national security, consumer protection and privacy. The sheer size of technology companies means that their greater responsibility could immediately have positive effects.

Today, I want to focus on a different aspect of the problem: If technological disruption leads to lower paid, less stable and fewer jobs, in an economy dominated by a handful of large technology firms, how do the majority of people participate in wealth creation and economic reward, including through more than just their labour?

I am not a Luddite – In fact I think the ledger of technological change weighs strongly in the positive.

Big tech’s record of innovation is real and its impact on our lives dramatically positive. From the superficial of arriving on time with Google Maps or organising a birthday with Facebook, to the more meaningful promise for the future in every sector from healthcare to transport and entrepreneurship.

Without dampening the white heat of technology, I would just like the transition to that future to be as short as possible, the inevitable dislocation and pain for people to be mitigated as much as possible, and the outcome of change to be as fair and socially cohesive as possible.

In the interest of time, I want to focus on two of the questions arising from tech disruption – for which I definitely do not have the answers.

The first is whether our analogue approach to competition, taxation and regulation needs to be recalibrated for a digital age?

The second is whether the potential inadequacy of household incomes can be enhanced through the value of our data?

Technology and competition

Let me start with competition and the spectacular growth of the companies driving technological transformation.

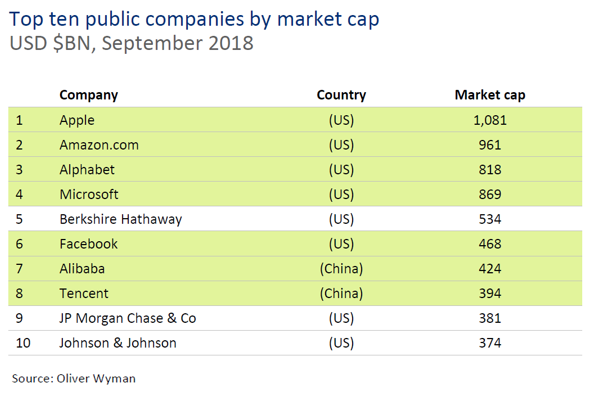

Seven of the world’s most highly valued companies are tech businesses – five American, two Chinese – and they constitute 30% of the value of the world’s biggest 100 companies. Five of these didn’t exist 25 years ago.

Grouping these companies together as we tend to is misleading. With notable exceptions, such as in cloud computing - they are careful about competing with each other, and each sits atop a market of its own, even while successfully entering multiple other markets. They tend to have comparators, not competitors.

They have overwhelmingly large market shares, enjoy large economies of scale and most have low marginal costs.

A significant part of their success is not just in the IP of their algorithms. It can be in the innovative audacity of their business models, where they curate and navigate consumers to sellers. It can be in the network effect where the value of a product to one customer goes up, the more customers who use it. It can be in the value of the data they collect, some of which could be subject to increasing returns over time, further reducing costs and raising barriers to entry.

Concentration in R&D and innovation

They also spend the most on R&D. At the start of the year, large tech firms accounted for more than 30% of all investment spending in the S&P500 and almost half of the absolute rise in investment.1

The drive to higher investment and innovation is very welcome, particularly when there is a clear and responsible approach, such as the Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan partnership on healthcare systems.

But the concentration in defining investment priorities by a small number of companies with a small number of agendas may have a societal impact worthy of a separate discussion.

From an economic perspective, the test must be whether they help disseminate innovation through the economy sufficiently. They can certainly reduce the cost of doing business, and of reaching customers for the traditional sectors, and contribute to an ecosystem of smaller companies.

But, are they also crowding out smaller players and holding back the take up of innovation?

Big tech certainly appear to have an instinct for acquiring innovative competitors, or occasionally using their scale to copy their ideas when they pop up in the so-called “kill zone”.

20 years ago – when I was an adviser in Government – we had a resonant debate on why “small pharma” and biotech didn’t grow to become “big pharma”.

But today, biotechs and start-ups are in fact powering extraordinary discovery. Rather than subdue innovation as we feared, the large pharma companies, by virtue of intense and direct competition with each other, create a “pull factor” for the IP and molecules discovered by small companies.

But tech giants do not compete with each other in the same way as pharma. In reference to the famous American monopoly of the 19th Century, Standard Oil – they are sometimes referred to as “Standard Commerce, Standard Social and Standard Data”.

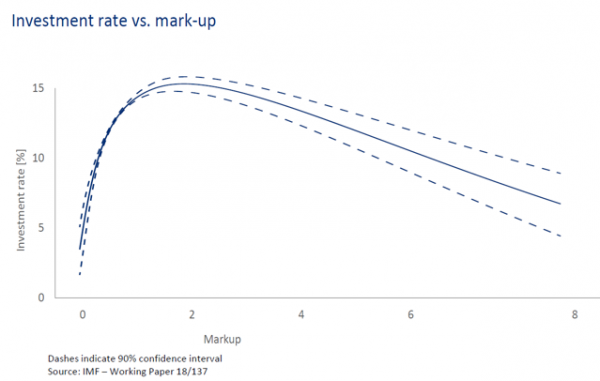

A recent IMF paper found rising industry concentration since the 1980s, accelerated more recently by a small number of “superstar firms”. And it noted that eventually, this is associated with lower investment overall in the economy. And a declining labour share of income - a subject I will return to for my second question.2

Competition policy

Let me first ask: are these companies’ natural – or should I say “network” – monopolies? Do they require large and dominant network effects in order to provide their current consumer benefit?

If yes, then should some of them be regulated as monopolies? As a minimum, not favouring their own goods and ensuring fair access to others on their platforms.

Even if they are not natural network monopolies, their financial power could suggest that their advantages are now locked in, and unlikely to be dislodged by the natural play of competition; this may warrant a competition policy response.

Other than for M&A, the focus of competition policy since the 1970s, particularly in the US, has been on ex-post remedies measured mainly by the short-term price effects on consumers, rather than the longer term impact on the market as a whole.

Two issues arise from this. First, the timescales involved in ex post competition rulings are very long.

Google’s search fine from the EU followed a 7-year investigation, and the appeal will extend this several years.

Second, these companies cannot be faulted for a lack of price competition. Indeed, they often charge nothing in money terms or have an undisputed record in delivering lower consumer prices.

A predatory pricing investigation is difficult if there is no price being charged.

Some argue that the measures of harm in competition policy – whatever they are – are secondary to more fundamental principles of concentration of power, fair markets and a level playing field.

As Senator John Sherman put it in 1890, “if we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessities of life.”

If ex-post competition policy is not nimble enough, it becomes harder for new entrants to compete, the longer the dominance of the incumbents is left unchecked.

So, as some argue, should the measures of economic harm from concentrated markets move beyond ex-post regulation, to include supply chains, long-term incentives for innovation and barriers to entry for challengers?

When it comes to M&A, technology moves quickly and blurs lines, making it difficult to define a market. This makes the scrutiny of market power, horizontal and vertical integration challenging. Policy is weak with respect to potential competition.

We also need to consider the application of other kinds of regulation, outside of competition policy, that traditional companies are subject to but that the tech companies disrupting them are not, creating an uneven playing field.

In China, where the penetration of Alipay and Tencent into payments is a dramatic 85% – Chinese regulators have been unafraid to subject them to regulation.

Again, I would caution that the tech firms cannot be grouped together despite some similarities.

Deeper analysis may conclude that one search engine’s dominance makes it an effective network monopoly, while another social network may be more susceptible to churn as preferences change. It is salutary to look back at one newspaper headline from 2007 – “Will MySpace ever lose its monopoly?”3

The question also naturally arises as to what can be regulated at national level – which could be confined to behavioural remedies in markets that can be nationally defined – and what can only be done structurally at the supra-national or global level. However, strategic competition on technology between Washington and Beijing may to lead to protectionism rather than coordination.

European regulators have been leading the way. GDPR has set a benchmark for regulators in other parts of the world to follow. But it is not perfect and has benefited some big tech firms who have found it easier to comply with than many traditional companies.

My concern is, in learning to ride this particular tiger, there is insufficient debate and analysis to understand the impact of these market dynamics.

We should therefore welcome initiatives such as the Treasury’s panel of experts, led by Jason Furman, which will be looking at exactly these issues about competition and technology.

Labour market trends

My second question is about arguably one of the most important disruptive impacts from technological change – that on labour markets.

The most basic method of economic participation is through labour – working for a wage.

But it is becoming clearer, that eventually it will be at least technically possible, to automate almost every job for which we get paid. What will be the price people can command for their labour in a world in which the reach of automation continues to grow? Where does that lead in terms of security of livelihoods and social inequality?

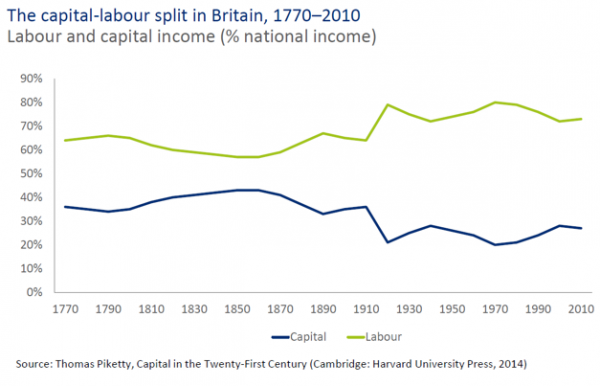

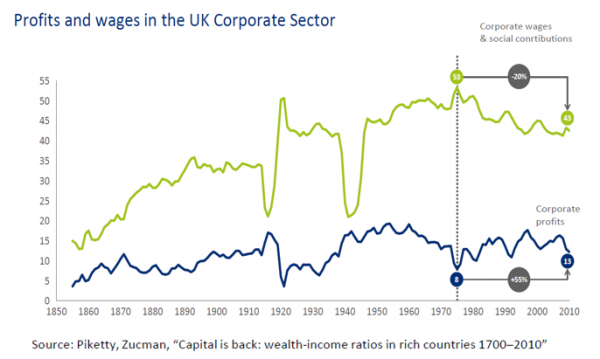

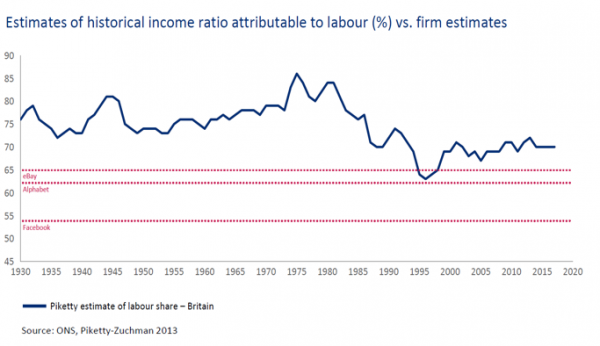

Since the 1970s, we’ve been experiencing a structural trend in the UK, and across the G20, in which labour’s share of national income relative to capital is reducing.

Notwithstanding recent improved figures, corporate wages and social contributions have been falling, while corporate profitability has risen.

Indeed, we are living through the longest period of real wage stagnation in 150 years. Not dissimilar to the Luddite generation.

Having a job used to provide a route out of poverty. But in the UK, more people in poverty now live in working households than in non-working ones.4

In the 20th century unemployment was the key indicator of an economy’s health. Perhaps in the 21st Century the key indicator should be the level and quality of wages and household incomes.

Any serious discussion on corporate responsibility must be seen in this context.

Returning to the influence of the big tech companies, they are not the architects of this problem. Although they do tend to create fewer high skilled, high paid jobs, and indirectly, create multiples more lower skilled, lower paid jobs.

Labour’s share of income at big tech companies tends to be below the national average.

When Instagram sold to Facebook in 2012 for a billion dollars, it employed just 13 people.

There is a wider set of policy responses, which may be discussed this afternoon. Personally, I am sceptical about the traditional go-to response of skills. While essential for many reasons, I am not sure skills is the answer to a reducing number of high skilled jobs.

I want to explore an admittedly narrow and partial solution of whether people can participate in the new economy, and supplement their labour through the value of the data, that they themselves create and own?

The nature of data

The public debate has understandably focussed on the privacy rather than the economics of data.

At present, data is perceived to be available in the public domain to any company as free raw material, subject only to privacy terms and conditions.

The data we produce is considered valueless to us individually. The value is largely created at the point of aggregation.

Furthermore, it is non-standard – there is no such thing as one unit of personal data.

It is non-fungible, no two individuals’ personal data is the same.

It is partly non-rivalrous, it does not become depleted through use.

And it does not have a unique quality, which means that it can be used by more than one company.

But none of these should necessarily imply lack of economic value.

Data is an essential human input powering algorithms, which we replenish every day. Every time we speak to a virtual assistant, tag a friend, or pick the top search result, we are enabling machine learning to become more intelligent and more useful.

Understanding the shopping habits of a billion daily users generates a certain amount of ad revenue today, but there is also future implied value from artificial intelligence.

Indeed, some data, a little bit like capital, can actually have increasing returns as the more complex higher value problems of AI need greater volume, variety and velocity of data.

So, data could perhaps be seen as a sort of capital or asset of the individual that companies can buy or rent, or even the labour of a willing and enthusiastic workforce. In any event, it has the possibility of giving people a stake in technological disruption.

Valuing data

But how do we value data?

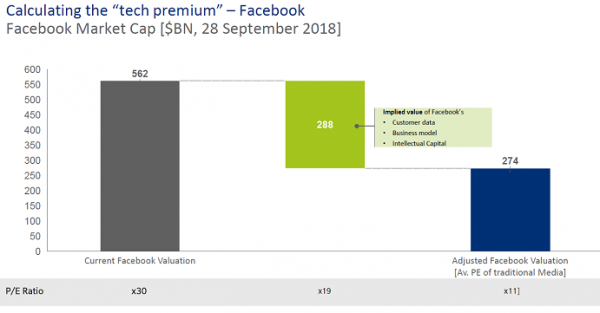

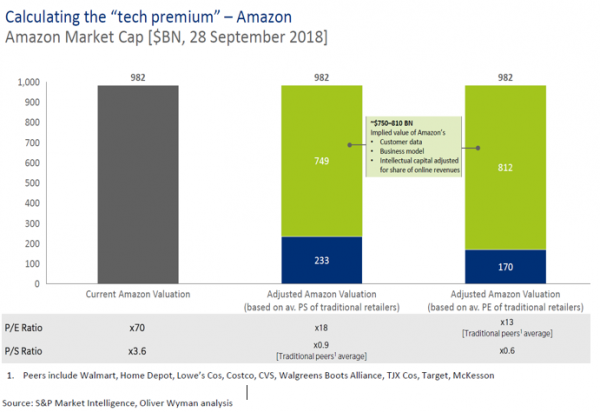

Big tech companies create a unique value from a combination of three factors:

- the scale and variety of the data they aggregate and their processing ability to refine and enrich it;

- the innovation of their algorithms; and

- their ability to attract and lock in subscribers with the network effect from their platforms.

But this cannot obscure the fact that they pay little for data as a raw material.

Rather they are actually paid in it, when it is traded for a service that is “free”. But as the saying goes, if you are not paying for a service then you are not the customer, but the product.

Oliver Wyman’s research estimated a “tech premium” of the tech companies relative to their nearest traditional rivals, ranging from $300bn to $800bn. This is of course a crude demonstration of what we anecdotally know to be true: that at least part of this value is based on the vast amount of user data they collect and hold.

Oliver Wyman also estimated that the value of data to the individual ranged from almost nothing to hundreds of pounds per annum, depending on the methodology.

Ultimately, the value of our data needs to be determined by a buyer. Particularly if the seller has reduced choices from lack of competition and there is inherent asymmetry of information between the consumer and the aggregator that prevents fair price discovery.

Sharing the value of data

So the next question is, whether some of this value should be shared with individuals as its creators, and in what way?

If compensating or substituting for labour, and viewed as a private good, a fee could be paid directly to individuals.

As a starting point, Tim Berners Lee’s most recent venture – called Solid – gives users the power to take control of their data, storing it in a single location and deciding who should have access to it.

But, the complexity of direct payments could be prohibitive.

If viewed as a public good, a collectively owned “data commons” could pool a community’s data, receive value in a license fee and distribute it through a dividend.

The purest form of treating data as a public good would of course, be through the tax system, through some kind of data royalty.

The current tax system is also analogue, and has allowed many tech firms to effectively pay lower tax than the corporate average.

The need to level this out is leading the EU and – as we saw earlier this week - the UK to challenge the methodology of tax at the point of value creation – in analogue terms the point of manufacture. In the absence of international coordination, this is meant to be a temporary revenue tax at the location of the user.

But the potential for unintended consequences in a revenue tax is high. And the chances of international agreement to improve it are low.

If the tech companies want a smarter system, they need to participate in finding a smarter answer.

In all cases, we need to be careful not to raise additional barriers to entry, stifle innovation by the incumbents, or clash with societal concerns and make data privacy a luxury item for the wealthy.

A more market friendly solution could follow in the footsteps of Open Banking or PSDII and open up access to the data held by the big tech companies, and to their infrastructure through greater use of open systems, open sourcing and APIs. But regulation would need to ensure a level playing field with common standards, portability and interoperability.5

And this brings us neatly back to competition issues. Would a market-based solution really disseminate technological take up and create better paid jobs?

Conclusion

Whether through competition, data, technological dissemination or productivity, it may be that market forces will eventually distribute the value created by the new economy in a fair and equitable way.

However, in learning globalisation’s lessons of disenfranchisement and anger, I question whether we can afford to wait for the decades it might take for this equilibrium to be found.

Instead, we could proactively analyse the impact of the size and concentration of the big tech firms in the overall economy, consider recalibrating competition policy to reduce the disadvantages of ex-post regulation, and more rigorously examine the potential competition impacts of integration.

And we could debate ways to reverse the trend in household incomes and create a more direct stake for people in technological change, including through the value of their data.

The conditions for solutions involving global cooperation between governments, tax authorities and regulators are distinctly weak. That leaves a vacuum for corporates to step up, to show leadership and regain the trust of the public.

Tech companies may see the gains of the status quo as overwhelmingly more valuable, certainly in the short term, than discussing and mitigating concerns around their financial and social power.

But leadership in a time of disruption would suggest to me that this is not the wisest course.

To sustain the gains of wealth creation and the potential of future discoveries, big tech companies and all business leaders... they and we... should lead the way in ensuring that the forces of the changing economy are managed well and the benefits widely shared.

1 Refers to R&D spending in Q1 2018 of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Intel and Microsoft, The Economist, 24 May 2018

2 IMF Working Paper 18/137, June 2018

3 The Guardian., February 2007

4 Commission on Economic Justice, Final Report, IPPR, September 2018

5 HMT’s expert panel will also look at these issues of data portability